“It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature.”

– Henry James

Thanks to their tireless efforts, and passion for our city’s history, Evelyn Montgomery, Ph.D. Director and Curator for the Old Red Museum of Dallas County History and Culture, along with Robert Prejean, Southwestern Medical District Manager and Urban Planner have created a short, but powerful read, this book will provide a great synopsis of the ebbs and flows of Harry Hines and the Medical District. A story that continues to change until today, as new buildings are constructed, new students fill classrooms, and an aging population needs care; the District will continue to evolve with the people that experience it on a daily basis. Here is a brief summary of those efforts.

Three major hospital and educational systems sit in the center of this busy, urban area of Dallas: Parkland Health and Hospital System, Children’s Health Dallas and the UT Southwestern Medical Center are all surrounded by well-established businesses, higher education institutions, non-profits, and residential neighborhoods, but it started small.

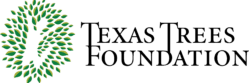

Beginning in 1874 the city maintained a City Hospital downtown, a government-funded facility for treating the indigent that would later be expanded via the addition of a relocated old schoolhouse, while a new building was planned. Every hospital and quarantine or convalescent facility built by the city and county outgrew its facility sooner than expected, and by 1887, the mayor of Dallas would announce the acquisition of 45 acres north of the water reservoir. The city never did anything to develop what was called North Dallas Park, and in 1893 sixty-five acres of the unused parkland was dedicated to new city hospital facilities, eventually leading to the obvious name: Parkland Hospital.

A grove of trees, including Pin Oaks still sit on the grounds, mimicking the earlier frontier landscape. The fashionable Colonial Revival style of Parkland when it was built represented the latest in hospital design; the pavilion concept allowed for maximum light and air, along with the separation of patient areas with long, thin wings of rooms instead of a massive, centralized building. For forty years the hospital expanded and changed.

The second Parkland location in the Medical District would reveal a grouping of medical facilities. The Dallas Morning News termed this grouping “hospital row” in 1926. The Woodlawn Hospital, or the “pest house” as it was commonly known (that name actually appears in official records and in the newspaper) housed tuberculosis patients among the many isolated there until the 1940s, when the threat of TB ended. From 1960 onward, the hospital was for general convalescents, the aged, alcoholics, the hearing impaired, and obesity patients. Woodlawn closed in 1974 and its operations were moved to Parkland.

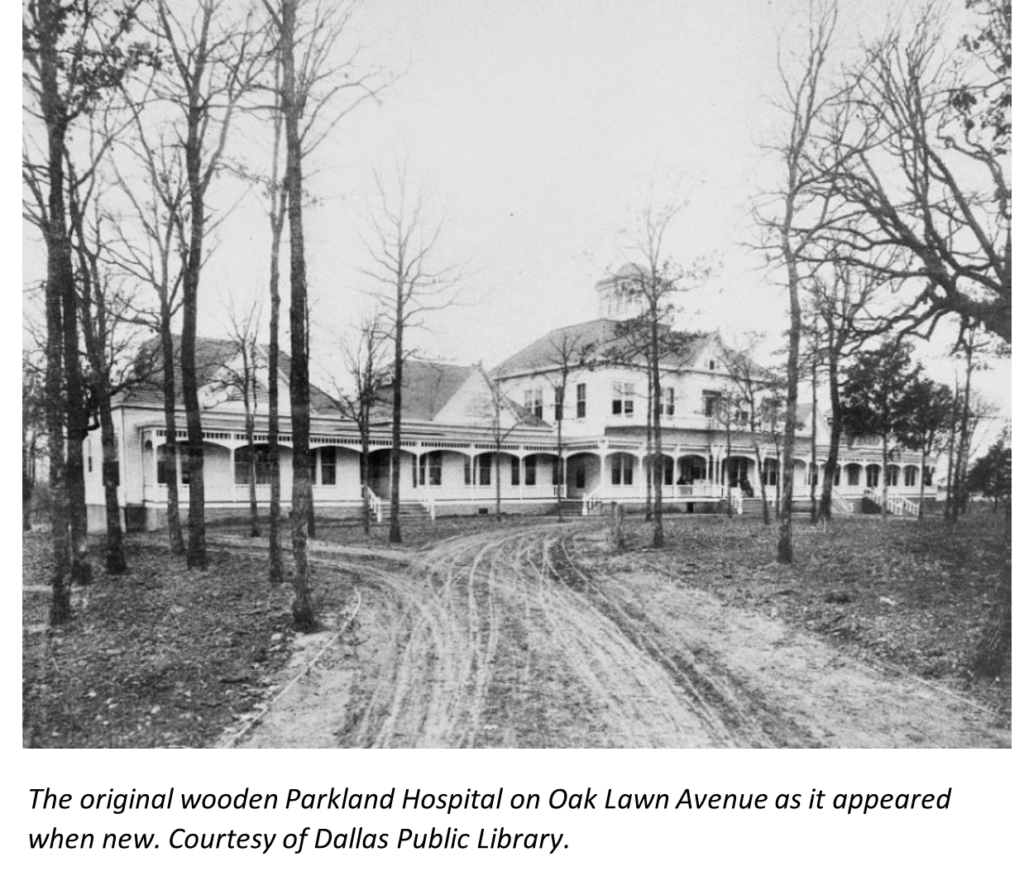

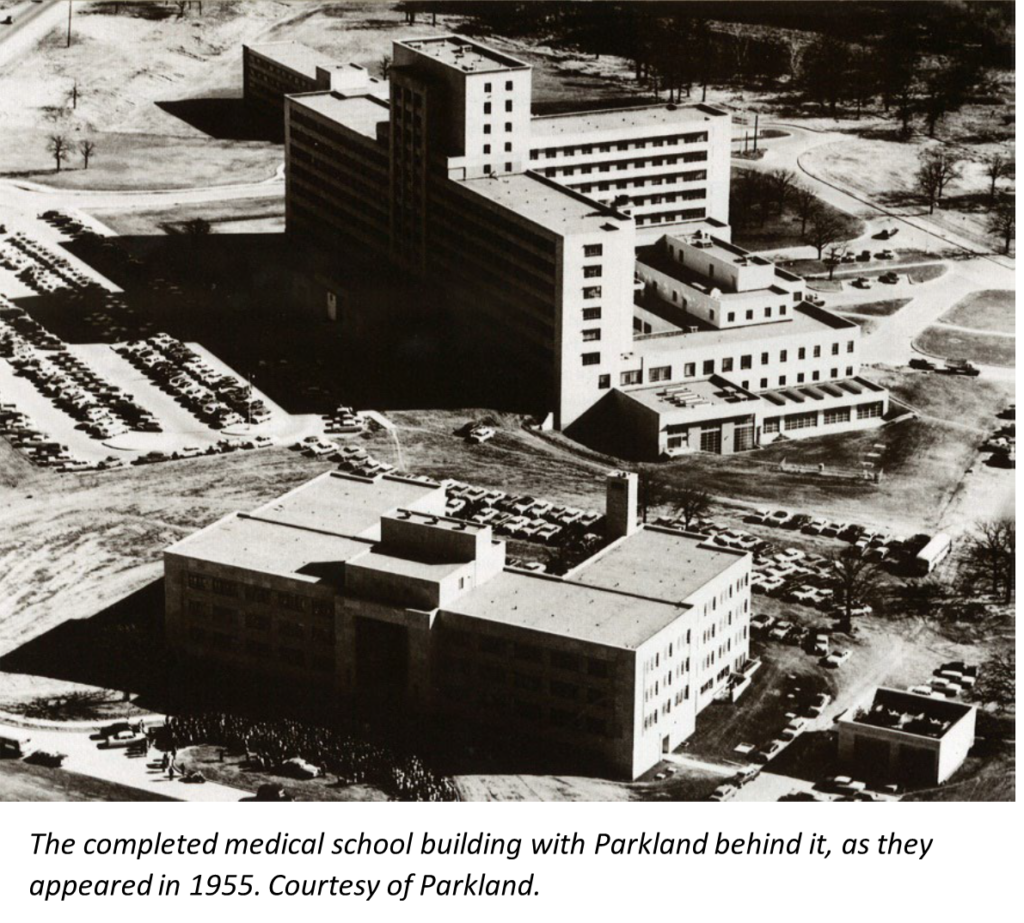

The hospital may have started small, as a city facility, but now is run by the County. Parkland opened at its new location on Harry Hines in 1954, but that was abandoned. Unexpected increases in material and labor nearly doubled the cost to build the hospital. It was locally known as “Old Parkland” until 2006, when Harlan Crow purchased it and restored it as an office park. In 1962, at the new Harry Hines location, Parkland’s emergency room adopted a model system, divided into six treatment areas that sorted incoming patients, using the nation’s first nurse-directed triage system. That emergency room would later be the subject of national scrutiny when John F. Kennedy was rushed there on November 22, 1963. Finally, in 2015 Parkland’s fourth, and most futuristic of its buildings opened. The building’s facade resembles the sunset on a cloudy day.

The legacy institutions of the Southwestern Medical Foundation give the District its current name. It began as an effort to establish medical training in early Dallas. Texas was the frontier. Formal medical education barely existed and required little training or experience until the late 1800s. The first significant attempt at a medical school in Dallas was the early Baylor Medical College in an abandoned building, initially called the University of Dallas Medical Department, though a University of Dallas didn’t actually exist.

Dr. Edward H. Cary helped open a new facility near the second location for Parkland Hospital with a new mutual arrangement of hospital training for medical students. Cary had connections among Dallas’ political and business elite, and experience at building facilities and challenging existing standards. In 1923, he and investors built the Medical Arts Building at St. Paul and Pacific. An 18-story building, it held medical offices and hospital facilities. It was quite visible in the city at the time. Cary became a local and national leader in medical organizations. Karl Hoblitzelle, a real estate investor who helped build the successful Interstate Theater Company that provided entertainment throughout Texas and neighboring states, donated 62 acres of land in 1945 at the tract on the south side of Harry Hines at Inwood; one of his many philanthropic donations to the Foundation. Mr. Hoblitzelle was its co-founder and remained a major donor, actively involved in leadership. Dr. Cary also helped establish the college-official designation, it became the second medical college in the University of Texas system in 1949.

Esther Hoblitzelle was a devoted collector of fine and decorative arts. When she died in 1943, she left that collection to the Hoblitzelle foundation, which gives extensively to medical organizations, as well as to art, history, and the indigent. On his giving, Mr. Hoblitzelle once stated, “I am inclined to lean toward programs which in general involve the discovery, transmission, and extension of facts, thoughts, ideals and ideas.” At his death in 1967, he left an estate valued around $17 million to the foundation.

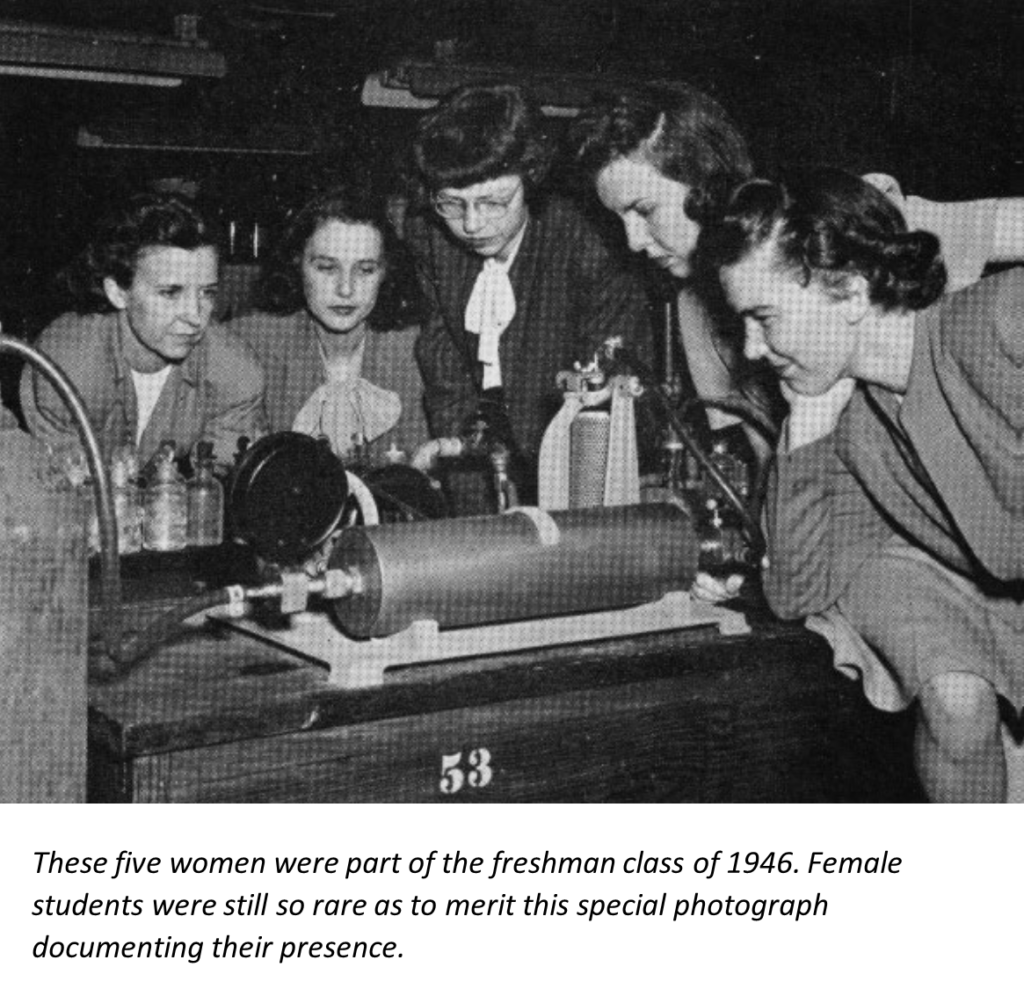

Parkland and the Southwestern Medical College were partners that relied on each other. Parkland would provide patients that gave students practical experience and the College provided affordable medical education. By the end of the 1950s there were 100 full-time faculty members, 400 students and 100 clinical residents. By the 1970s, the school added 1.5 million square feet of construction, and faculty grew to 500, with 800 medical students, (Image to the left courtesy of UTSW Medical Center).

As the college expanded with more research and teaching hospitals, a new name was forged, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. And in 1985, Doctors’ Joseph L. Goldstein and Michael S. Brown were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries about the metabolism of cholesterol. It was the first such honor awarded in Texas. The Nobel committee would again recognize the Center’s work in 1988. Dr. Johann Deisenhofer shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. And again in 1994, Dr. Alfred Gilman would bring Nobel recognition to the Center. In 2011 the organization removed “in Dallas” from their name and became The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. They won another Nobel Prize and started construction of the William P. Clements, Jr. University Hospital.

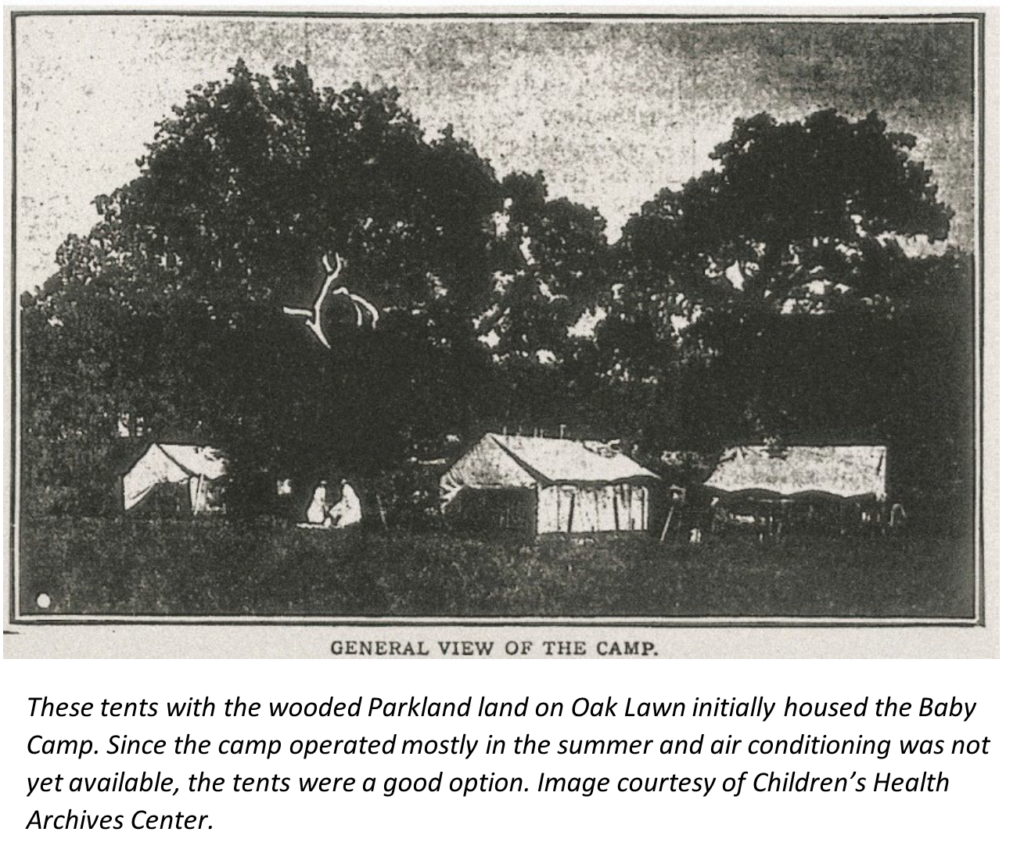

The “Baby Camp” housed on the grounds of Parkland Hospital’s original location on Oak Lawn, started out as a series of tents supervised by a relocated Parkland nurse, Miss Smith, where local doctors volunteered their time. It was the first remnants of Dallas’ early care for its children.

By 1915, a permanent hospital was provided to replace the camp, the Baby Camp Cottage, located across Oak Lawn from the original tent site. Miss Smith continued to operate it and over the next few years she was visited by a little girl she had nursed to health; little Elizabeth Bradford. She would bring toys to the babies when she visited in her pony cart, but as a young mother, she was killed in a car accident. Her father, who had earlier lost his wife, built Miss Smith a hospital in their memory. The Bradford Memorial Hospital for Babies opened on New Year’s Day in 1930. The new hospital was a large stone building with new equipment, in fulfillment of May Smith’s wishes.

That generous donor, Thomas Leonard Bradford was elected to the first Dallas City Council in 1930, and his fellow council members elected him mayor. His son continued the family tradition of generosity for public health. In 1947, he donated the twenty-three room mansion his father built along the Cedar Springs Road to the Pilot School for the Deaf. Deaf children learned in the house and played on its grounds until 1966. The school joined other medical institutions by moving to the Medical District. It became the Callier Center for Communication Disorders located on Inwood Road. It is now part of the University of Texas at Dallas system.

Meanwhile, the Presbyterian Clinic, which would become the Richmond Freeman Clinic, also took their charitable ministrations directly to an impoverished area. Woodchuck Hill was across Oak Lawn from Old Parkland, the area later occupied by Reverchon Park. First Presbyterian Church originally opened their clinic in the church basement in 1921, with a kitchen table serving for a treatment surface. They had one doctor, two volunteers and the church pastor for a staff. The new hospital on Maple, in what is now the northern corner of Reverchon Park used only the Richmond Freeman Clinic name after 1935. It was an education-oriented operation with trained nurses and volunteers who were sent out to the homes of the poor. Then, in 1938 the same benefactor who made the Freeman clinic possible donated land right next to it, and in 1939 construction of the Texas Children’s Hospital, soon renamed Children’s Hospital of Texas, began. The facility opened in 1940 with 47 beds.

The budding institutions that would make up modern Children’s Medical Center Dallas: the Bradford Hospital, Richmond Freeman Clinic and the Children’s Hospital of Texas. Each began by serving underprivileged patients. The first steps toward future consolidation happened in 1941 when they created an umbrella institution, Children’s Medical Center, which included Hope Cottage for orphaned children. The Freeman clinic assumed most outpatient services, inpatient care for children over two years of age took place at the Children’s Hospital, while infants remained at Bradford. They also began to combine their educational efforts and in the 1950s, those efforts grew to encompass formal teaching and research, with increased interest children’s behavioral studies.

The growing Southwestern Medical Center welcomed the relocated Children’s Medical Center in 1967, with a new eight-million-dollar facility on Amelia Street, now Medical District Drive. The Freeman Clinic relocated inside the new structure. The third floor housed the Bradford Memorial Hospital. The recently expanded butterfly atrium lies just on the other side of the hospital’s repurposed main entrance, a 17,000-square-foot courtyard with a primary function of reducing stress and anxiety for staff and visitors; it has built in musical instruments and 3,000 square feet of shade canopies that resemble a butterfly’s wings when viewed from the floors above.

Through a partnership with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Texas Tech moved their Doctor of Pharmacy program in order to collaborate in the Medical District with several of their DFW partners like UTSW, Children’s Medical Center and Parkland Health and Hospital System, offering postgraduate training for specialty practice and research careers. The pharmacology laboratory was moved to the SW Campus in 2011 to, according to their web page, enhance their research and training programs and to form alliances with cancer centers here in DFW, and other leading cancer researchers in the region.

The TWU T. Boone Pickens Institute of Health Sciences – Dallas Center opened in February 2011, combining the university’s Parkland and Presbyterian sites into an eight-story, 190,000-square-foot building in the heart of the Southwestern Medical District. The Dallas Center is named for Texas oilman and entrepreneur T. Boone Pickens, who donated $5 million to the building’s fundraising campaign. The center houses the Houston J. and Florence A. Doswell College of Nursing, the TWU Stroke Center – Dallas, and the university’s physical therapy, occupational therapy and health care administration and business programs. The building is Silver LEED Certified, in keeping with the university’s goal of reducing its carbon footprint and even requires green cleaning products. According to their website, academic programs focus on the use of innovative teaching methodologies and practice laboratories that offer work place simulation environments to give students real-world learning experiences.

“A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history.”

– Mahatma Gandhi

To conclude this summary, so many individuals have put sweat and tears into making the Medical District what it is today. Dr. Edward Cary, Dr. Onesimo Hernandez, and Miss May Forster Smith dedicated their lives to it, just to name a few. Donors like Karl Hoblitzelle, Thomas Bradford and Richard Freeman made such incredible financial contributions, dollars spent can still be seen on the landscape; at Parkland, the names of donors are permanently etched in glass panels on the two-story, glass atrium main lobby. Without failing to mention the countless hours of volunteered time and donations from local families and businesses, a book of less than a few hundred pages still only touches on the entire history of this area. With the Green Spine and Green Heart Park, the Texas Trees Foundation is building upon the natural elements that once were the Medical District, to restore some of the ecological benefits that can mimic that connection to nature but also that sense of community that the District’s past residents ushered in; balancing the needs of the forty-plus thousand persons that make up the Medical District and all of the other general medical support services that make it all possible, having a shared space and shared spaces for all to enjoy, is of crucial importance to the Foundation and the many stakeholders planning this transformation, to reconnect to nature and to each other, and uplift the health and well-being of all District users.