“Biophilia is humankind’s innate biological connection with nature. It helps explain why crackling fires and crashing waves captivate us; why a garden view can enhance our creativity; why shadows and heights instill fascination and fear; and why animal companionship and strolling through a park have restorative, healing effects,” (14 Patterns of Biophilic Design, Terrapin Bright Green, 2014). Biophilic design, inherently Indigenous design, are practices that have been used for centuries; designs shaped by the earth’s materials, influenced by human health and wellbeing. To plan for inclusive biophilic cities, it’s important to remember the removal of Indigenous persons from lands that cities are on; planners must acknowledge the history of colonization and the impact of dispossession. Planning for nature spaces means welcoming interested Indigenous peoples into the design process, as an opportunity for reclamation of a lost connection to a place, (On belonging and becoming in the settler-colonial city: Co-produced futurities, placemaking, and urban planning in the United States, Barry and Agyeman 2020). Equitable biophilic city planning means designing with an understanding of not only the needs of community members, but also by considering both equitable distribution and design of nature, (American Planning Association, Planning for Biophilic Cities, 2022).

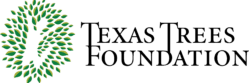

Cully Park

Humans have been practicing biophilic design for thousands of years, building shelters with only the materials they could find; they helped people stay warm or cool, protected them from weather or animals, and helped to preserve or cook food, and to hold belongings. Aside from the practical applications, they were expressions of culture, that not only reinforced but also reflected traditions and spiritual beliefs. The planning process for Cully Park in Oregon included consultation with local tribes that once occupied the land. The final park design includes a 36,000-square-foot Inter-Tribal Gathering Garden that provides a place for ceremonies, teaching, and growing traditional plants. To lay the foundation for equitable biophilic city planning, understanding the needs of community members and considering both equitable distribution and design of nature is crucial, (American Planning Association, Planning for Biophilic Cities, 2022).

Housing Designs

The Gurunsi are one of many ethnic groups in western Africa. Their earth houses are excellent examples of structures that utilize local materials and act as avenues for cultural expression. Round, rectilinear, and adapted for harsh climate, they are made from a mixture of clay, straw, and cow droppings. The walls are constructed with only a few openings so that they stay cool during the day and remain comfortable in the evening. Paintings could be found on every square inch of the exterior with symbolic patterns, scenes from daily life, and animal motifs, (Sturgeon, The Evolution of Biophilic Design. 2017)

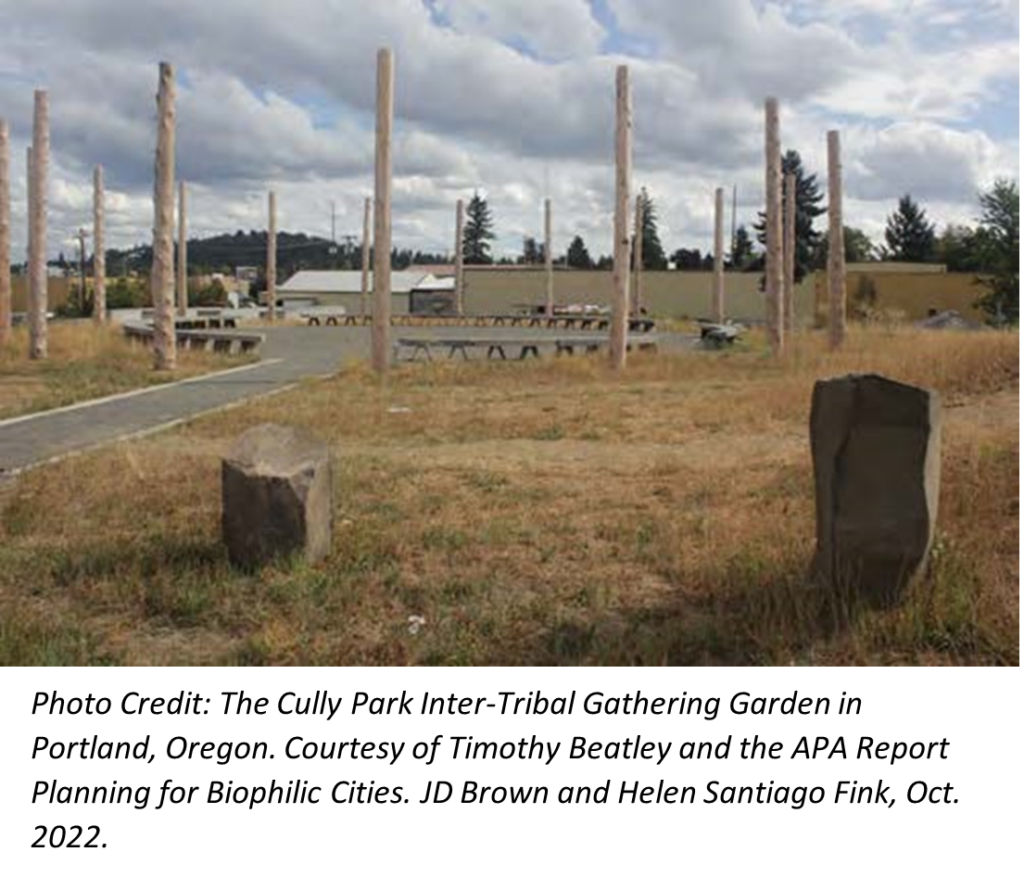

American Indians built many types of dwellings throughout North America that reflected a specific tribe’s lifestyle and regional climate. From wigwams and tepees to longhouses and grass houses, these were all made from earth-based materials, showing their respect for the land. The Algonquian Indians of the New England Woodlands and Eastern Canada built fairly small wigwams that were easy-to-construct with a wooden frame. The Iroquois built longhouses similar to wigwams, but they could measure as long as 200 feet and hold up to 60 people: revealing a cultural expression of significant community values.

Designers, like Frank Lloyd Wright, dedicate their entire careers to creating climate-adaptive, place-based buildings. His creation, ‘Fallingwater’ was built into a waterfall in a forest as an example of a place created in response to its site, which promotes interactions between people and nature. More importantly, Indigenous architecture shows how we can create shelters in response to climate by using the resources nature provides.

Indigenous education and biophilia, Children and nature in Tukum Village

Educational experiences of Indigenous children can also teach us how to build and design, especially schools and other types of learning or interactive environments. A study was performed to access the cognitive and affective aspects of Indigenous children’s perception of the environment, based on the understanding that daily and direct contact with the natural world leads to a pro-environmental predisposition. Fifteen students, age 8-10, and their teacher from an Indigenous school in Brazil participated. Children’s perceptions and feelings about nature were accessed from their drawings and interviews, along with video records of interactions between children and natural environments outside. The children’s teacher was also interviewed about teaching strategies used in daily activities.

The children’s drawings showed their affinity for trees, the river, and the school. Moreover, the children signed with both their non-Indigenous name and their Indigenous one, which refer to animals, plants and other aspects of nature; the simple fact that they use these names reveals their people’s closeness to nature. Many of the pictures showed people and elements of the built environment suggesting that the children didn’t see people as separate from the natural world. The researchers concluded that daily life in natural environments as experienced by Indigenous children through both their culture and school promotes biophilia and environmental awareness. They suggest that the Western model of education which tends to promote the gap between children and nature would do well “to take inspiration from Indigenous education in order to promote biophilia and the prevention of health and mental problems among urban children,” (Profice & Santos, Children and nature in Tukum Village: Indigenious education and biophilia, 2016).

Indigenous Tribes in Dallas and the SWMD

Dallas’ Medical District was once home to Indigenous peoples. Just northeast of where the Trinity River once flowed through the District, was the Blackland Prairie, a clay-rich soil that made the prairie and the edge of the Cross Timbers a good home for cottontail rabbits, antelope, deer, bears, and wolves. The availability of these plants and animals, and water, made the area attractive to Native Americans. Fragments of Nocona Plain ceramics found there show that southern plains tribes once may have inhabited the area. Evidence of early agriculture and bison hunting have also revealed their presence there. The Keechi tribe of the Caddoan language family built a village along Cedar Springs Creek (Southwestern Medical District History Book, DRAFT, Montgomery, Prejean, 2022). The Wichita tribe and their affiliated groups, the Waco, Taovaya, Tawakoni and Kichai (Keechi) collectively were referred to as “the Wichitas,” (Derby Historical Society, The Wichita tribes were early farmers, 2021).

Designs shaped by climate, available materials, and culture illustrate the effective ways humans have evolved, adapted, and inspire each other. Though most modern buildings are designed with cost as the main driver, biophilic design influences design decisions by making human health and wellbeing the main driver. By utilizing biophilia in the streetscape and park design, we give value to those that were here before us and the building practices they so long ago vetted.

References

Bill Browning & Terrapin Bright Green. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Wellbeing in the Built Environment, 2014. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/14-patterns/

Derby Historical Society, The Wichita tribes were early farmers. September 25, 2021. https://derbykshistorymuseum.org/blog/f/the-wichita-tribes-were-early-farmers.

Janice Barry & Julian Agyeman (2020) On belonging and becoming in the settler-colonial city: Co-produced futurities, placemaking, and urban planning in the United States, Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City.

Evelyn Montgomery & Robert Prejean, Southwestern Medical District History Book, DRAFT. November 2022.

JD Brown and Helen Santiago Fink. American Planning Association (APA), Planning for Biophilic Cities. October, 2022: https://www.planning.org/publications/report/9255203/#:~:text=PAS%20Report%20602%2C%20Planning%20for%20Biophilic%20Cities%2C%20explores,the%20benefits%20of%20nature%20for%20individuals%20and%20societies.

Profice, C., Santos, G.M., dos Anjos, N.A., (2016). Children and nature in Tukum Village: Indigenious education and biophilia. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior, 4(6): https://research.childrenandnature.org/research/educational-experiences-of-indigenous-children-promote-biophilia-and-environmental-awareness/

The Evolution of Biophilic Design. Amanda Sturgeon. OCTOBER 31, 2017: https://gbdmagazine.com/the-evolution-of-biophilic-design/.

Marinda Griffin

Urban Design Associate